Sports cards have been getting a lot of mainstream media attention lately. Rising prices and record-shattering auctions set against the backdrop of the pandemic does make for a good story. There are new platforms for buying and selling and investing money that goes along with them, too. All of it has put cardboard in the spotlight.

Forty years ago at this time, there was a lot of attention, too. That was the year all heck broke loose in the once-quiet world of baseball cards. Topps’ long-running stranglehold on the MLB trading card market was over thanks to a judge’s ruling. Fleer — which had long sought to obtain a license — got one and so did Donruss, which had produced confectionery products and non-sports cards for years. It was a wild year, both on and off the field.

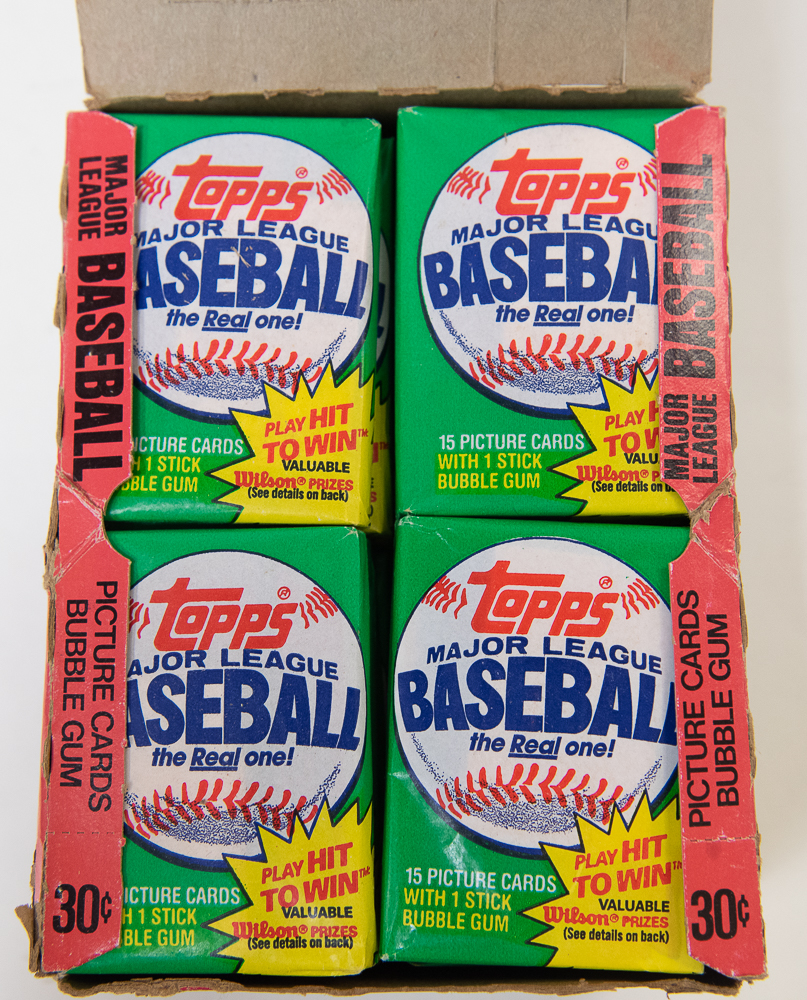

Collectors suddenly had three different sets to chase. Topps had taken a shot to the jaw and was now fighting to maintain its share of the pie. It even started putting the phrase “The Real One” on packaging, as if to combat confusion at grocery store counters. It was also a bit of arrogance.

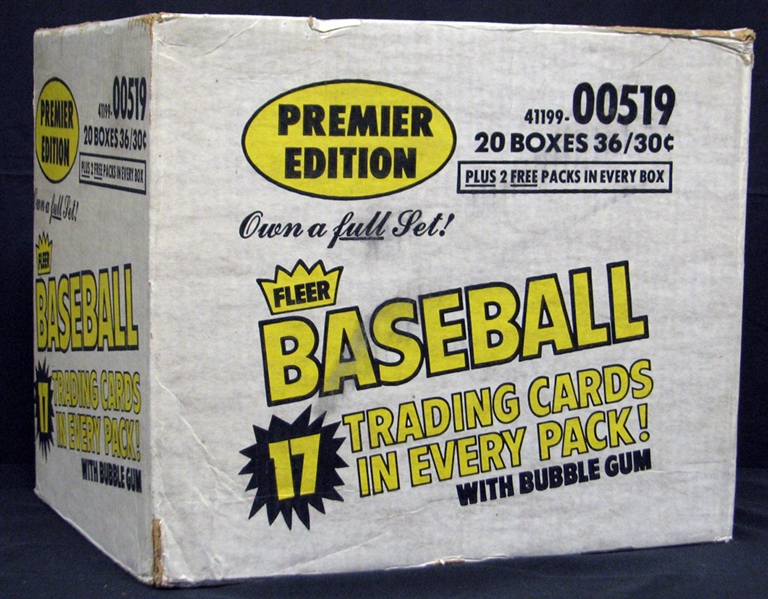

Fleer went the “better value” route by tossing in two more packs — 38 in a box instead of 36, with the two extras sandwiched in the middle of each box, between the stacks of packs.

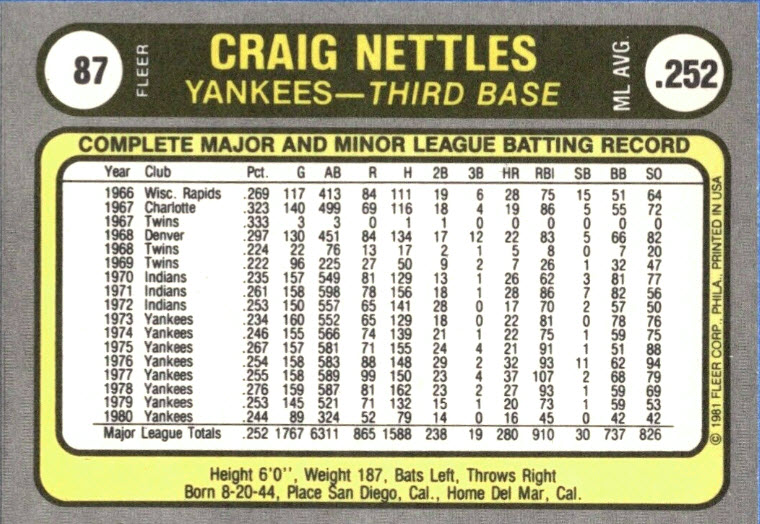

The rush to put cards out following a judge’s ruling that opened the door to competition resulted in a comedy of errors. Fleer’s proofreaders missed a bunch of mistakes. Most famously, the back of the first printing turned Graig Nettles, the well-known Yankees third baseman into “Craig.” They screwed up positions, used the wrong photos for some players, screwed up some stats, and called Fernando Valenzuela “Fernand.”

Donruss didn’t have quite so many glaring errors but if you’ve ever opened an early print run box of its inaugural issue, you can immediately see the problem. Collation was horrible. Putting sets together required a lot of boxes and a lot of trading. On the other side of the spectrum, Fleer’s vending cases — 500-count boxes of cards just like those Topps produced for years — were a master stroke of perfection. Open four boxes and you got three sets and some duplicates.

Dealers and collectors weren’t sure which set to buy so they sampled boxes of all three, but finding them was sometimes a challenge.

While the media buzz surrounding the new competition phase of the baseball card market was hot early in 1981, the tide turned later in the season when the players and owners couldn’t agree on a new contract and the players went on strike, interrupting the season. Suddenly, people were burning baseball cards in protest.

The card companies marched on, though, and in 1981 we saw our first Topps Update set, sold via small boxes rather than in packs. The sets were a hit and Topps would continue to crank them out as the years went on. Fleer did the same. It gave fresh, solo rookie cards to players who had only appeared on the multi-player prospect cards, smartly keeping Topps in the hobby news even after the season wound to a close in October.

There would be more interesting times to come before the decade was out as Upper Deck turned the hobby on its ear with (for the time), high-end cards that had a hologram on the back and the market went through another boom period. Manufacturers were more than happy to supply an unprecedented quantity, which led to a new series of issues.

The battle for cardboard bucks would continue for nearly 30 more years, until MLB opted to hand the exclusive license back to Topps but there was nothing like the first few months of 1981 when “Topps, Fleer or Donruss?” was part of the hobby’s new vocabulary.

Fleer and Donruss card stock was thinner and photos weren’t as sharp but who cared.